The Building of the Church

Menu

The evolution of the parish of Hawes

Early development of churches in the upper dale started with buildings in Aysgarth and Askrigg in the 12th century. Jervaulx Abbey was the patron of the parish and no doubt supplied some of the clergy. For centuries people in Hawes would be travelling to Aysgarth or Askrigg for services, baptisms, marriages and funerals. At this time the churches were under the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. The first priest appointed in Hawes occured in 1483 when Sir James Whaley ‘ in the first year of King Richard III ….(he) was appointed to sing at the chapelle of Haws in Wensleydale for one year, for a salary of seven marks’ (£4. 11s 4d). Hawes was part of the Manor of Bainbridge – which in turn was part of the estate of Middleham Castle, one of the residences of King Richard III. There was not necessarily a church building in Hawes at this time and it was not until the end of the 16th and beginning 17th centuries that chapels of ease were built in Hawes, Hardraw, Stalling Busk and Lunds. (all still in the parish of Aysgarth and with pastoral links to Askrigg). By now The Church of England was established with Henry VIII’s separation from Rome in the mid 16th C and the dissolution of the monasteries.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a marked increase in the population of the upper dale and Hawes began to agitate for parish independence. Robert Dobson who died in 1676 and buried at Askrigg is referred to as ‘the minister for Hawes’. From that time the names and dates of Clergy are known. The fight for ‘independence’ from Askrigg continued in 1680 with a refusal to pay the ‘Hawes Quarter’ and dispute resolution was sought in the ecclesiastical courts in Richmond and York, followed by the common law court in York. Despite this the church building in Hawes was still called ‘the chapel’, the minister called ‘curate’ and the administration of sacraments were still taking place at Aysgarth or Askrigg. The earliest records that survive containing baptisms, weddings and funerals in Hawes date from 1695.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a marked increase in the population of the upper dale and Hawes began to agitate for parish independence. Robert Dobson who died in 1676 and buried at Askrigg is referred to as ‘the minister for Hawes’. From that time the names and dates of Clergy are known. The fight for ‘independence’ from Askrigg continued in 1680 with a refusal to pay the ‘Hawes Quarter’ and dispute resolution was sought in the ecclesiastical courts in Richmond and York, followed by the common law court in York. Despite this the church building in Hawes was still called ‘the chapel’, the minister called ‘curate’ and the administration of sacraments were still taking place at Aysgarth or Askrigg. The earliest records that survive containing baptisms, weddings and funerals in Hawes date from 1695.

The old chapel

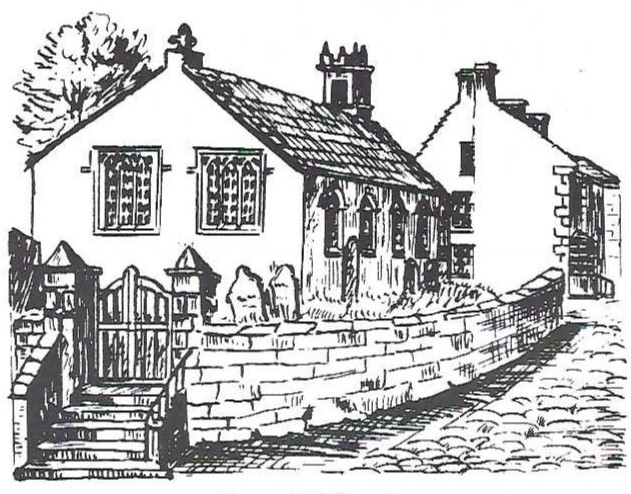

The old chapel building, probably existing from 1620, is best described as a ‘barn-church’ and was rectangular, quite low, and without aisles or tower (a good surviving example of this type may be seen at Chapel-le-Dale on the road to Ingleton.)

It was extended in 1712 by 10 foot and again had major alterations in the mid 1760’s including new seats and windows. The seating cost £100. The building was next to the roadside and opposite the White Hart and by now had two east windows, five windows on each side and a bell tower. There were two entrance gates – one by the shop and one by the White hart. The floor was stone flagged and there was a gallery at the west end.

However, as the Hawes congregation grew beyond its capacity to hold them, a new building became essential. The Diocese conceded the need in 1849 and planning followed and fund-raising began. Most of the money needed was raised quite swiftly – with a long and impressive list of over 200 donors. The foundation stone was laid on July 25th 1850.

Thereafter Hawes – in effect if not yet quite in law – ceased to be technically an adjunct of the vast and unwieldy ancient parish of Aysgarth, at that time the second largest in England, covering 81,000 acres. When, in 1870, the term Perpetual Curate ceased to be employed – over the years it had come to imply an inferior status – Hawes had, at long last, its own Vicar and freehold Vicarage.

The building of St. Margaret’s

Early designs of the present church

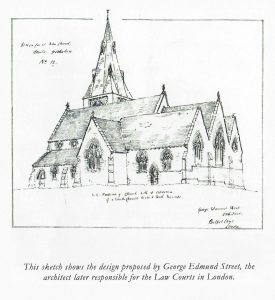

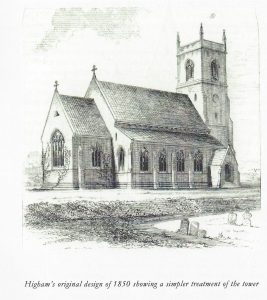

The work began on the present building in 1850 following plans drawn up by a Wakefield architect, A. B. Higham. He worked broadly in the so-called Decorated mode, which many apostles of the Gothic Revival – then at its height – considered the finest of all English church styles. Of far more interest is an alternative design – the church that never was – by a Victorian architect, George Edmund Street, who had only set up his own practice in 1849. Both original and prolific, he was soon to become very famous, influencing many major figures like William Morris and Philip Webb. His best-known work is the Law Courts in London and his vigorous church design with its transepts, triple aisles, large chancel and broach spire would, had it been built, probably have been his first major commission and, as such, would nowadays bring amateurs of Victorian architecture from far and wide. Perhaps it was too avant–garde for whoever made the choice or – more likely – it would simply have cost too much. Even Higham’s design, for such a rural church, is a large building, perhaps too large, and one cannot help feeling that maybe those who set it up on such a scale still had a bone to pick with Aysgarth. The church has Higham’s original design, dated 1850, then without its characteristic little spirelet topped by a weathervane on the tower. It seems it was initially meant to be sited where the old church stood. But in the event it was – we don’t know at whose instigation – set on its present hill-top site, from which it effortlessly dominates the town, and is visible in all directions for many miles. Nevertheless, it only cost £2,450, according to the contemporary accounts and specifications and only took about a year to build. Most of the workmen were local – a few others were brought in by the architect, who by the way got just £88.00 in fees. At the time Mr. Edward Moore made some interesting notes about the builders and their work-, of which a selection follows:

“The resident Architect was named Dixon, [he was in reality the Clerk of Works, paid £ 133 as ‘salary‘] and he lodged with Betty Scarr all the time it was building.

The builders’ names were Edmund Dick, Dick Fothergill, John Jeff and Lang Anty [probably a nick-name for Long- i.e .. tall -Anthony]; they had two labourers or hod carriers, Jimmy Kelly and Little Peter, both Irishmen. Jimmy stayed with the Hawes masons many years after the church was finished. The stone cutters or hewers were strangers. John Warren did all the woodwork, Bowes did all the glazing and Mike Dinsdale all the ironwork, Ralph Stockdale carted all the stone from the top of Snaize(holme] Fell; it was brought from the top down to the road in Lang Gill on a sort of sledge: [It can be inferred – as their names also suggest – that the last-named four men were local too. And certainly not all the stone came from snaizeholme, where there was none suitable for ashlared work]

When the last stone was fixed on top of the turret, Little Peter stood on it on one foot, waving the other and his arms to muse the spectators below. The hewers were continually pestered with women who went to pick up any tidy sized chippings of freestone to stone their floors with.” [To stone here means to scour].

Among other things, this entertaining account – how one would like to have met the daring Little Peter – shows us how relatively few changes in building practice had occurred since mediaeval times when stone was – wherever feasible – locally quarried, and horse-drawn “sleds’ used to drag it to the nearest road where wheeled wagons could take over, a back-breaking task for all involved, especially the unfortunate horses.

The old church which abutted on the main street at the foot of the hill was, of course, pulled down and its stones utilised by all and sundry, some doubtless for the new church. The Faculty for pulling it down insisted that all ‘usable slates’ should be set aside and re-used on the south [i.e .. less exposed] face of the new roof. Apart from this, few traces of it remain, except some rather undistinguished memorials to the wealthier local residents, which were transferred to the new building, and one or two other features which will be pointed out as they occur. The most ancient of the three grave-yards is that surrounding the church but we have hardly any really ancient tomb- stones, because the local stone used is subject to splitting and flaking in our – often harsh – winters, There remains just one ancient stone, to the right of the front path It dates from 1696 and – unsurprisingly- commemorates a Metcalfe. Both its stone and its rather crude lettering are evidently local, the work of Hawes quarrymen and masons.

Acknowledgements to

James Alderson (Under Wetherfell ). Drawing of ‘Old Church’ by Lily Alderson

and

Dr Trevor Johnson and Hugh Bridgman

Compiled by Mike Hirst

; ?>/images/cross.png)