War Memorial Stories – WW2

- Trooper Walter Brown

- Pilot Officer George Cockbone

- Corporal Jack Hindle

- Sergeant Pilot Sydney Kirkbride

- Lieutenant Frank Percival

- Major David Shorter

- Sergeant Keith Stevens

Parts of ‘Wensleydale Remembered’ are reproduced with grateful thanks to the author, Keith Taylor, and publisher, County Books

Trooper Walter Arnold Brown, 11th Hussars, Royal Armoured Corps

The Brown family have farmed in the Upper Dales for at least two centuries. Walter’s great grandfather, Robert, was born in Mallerstang, between Kirkby Stephen and Garsdale. After his marriage to Mary Kilburn, the family moved to Gill Edge, just south of Bainbridge towards Countersett and the family remained there throughout the generations. Walter was born there on 20th August 1917 to Edward and Annie (nee Brockell). He was baptised along with his elder brother Henry on 22nd March 1918 at St Askrigg Church. In addition to Harry, Walter also had two other elder brothers, Percy and John, an elder sister, Jenny.

Walter worked on the family farm first with his father and brothers, and after his father’s death, with his brother John. After the war broke out, Walter went down the mines near Durham as one of the ‘Bevin Boys’. Named after the former union official Ernest Bevin, who was the Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government, 10% of conscripts aged between 18-25 were chosen to be Bevin boys. In addition, some volunteered as an alternative to military conscription. Recruits were needed in the mines as the government needed to increase the rate of coal production which had declined in the early years of the war. Despite it being a dangerous and vital occupation, Bevin Boys were often targets of abuse from the general public who mistakenly believe them to be cowards or draft dodgers.

Walter did not take to working in a mine and enlisted as a trooper in the Royal Armoured Corps, as the driver of an armoured car. The 11th Hussars went into France after the D-day landings and took part in the Allied advance into Belgium and Holland. On 1st October 1944, Walter wrote home telling them that they had gone through Belgium the month before and had received a good reception from the population. He had had to drive with one hand on the steering wheel and the other taking in gifts from well-wishers. They were showered with beer and fruit and cheered by the children. He went on to say that they were now ‘somewhere in Holland’ and that he had had the opportunity to milk some cows and that the windmills were ‘a grand sight’. A letter in mid-December, tells of increasing shelling, and that this was becoming nerve-racking.

Walter was in 3 Troop, B Squadron and drove Sergeant McGuire, its commander. McGuire was a decorated soldier, having won the Military Medal earlier in the campaign and on 28th November he had been presented with his ribbon by Field Marshal Mongomery. The 11th Hussars were near Bree in Holland but at the start of December they moved to the Maaseik and Ophoven area, on the river Maas. They were due to cross the river to go into the line at Roosteren and Illikhoven. B Squadron were responsible for about 3000 yards of the front, with no defences except the Juliana canal, whose bridges had been blown. The plan was for each patrol to form a strong point at night and try to observe by day, without being seen. In support were around a 40 strong contingent of the Dutch Resistance, who were equipped with all sorts of German weapons which they had captured. Every so often, B squadron would get 4 days leave, often spent in the hot baths of a nearby colliery – a chance for a general clean up; and the opportunity to see a cinema show or two.

On Boxing Day 1944 at 5am, gunfire and machine gun fire began when the Germans attacked D Squadron in Gebroek village. They overran the village, but the troops managed to get out with only minor casualties. No 3 Troop were sent to Illikhoven to watch the canal in case the Germans attempted to cross it. A few shells burst around their position and one landed on the house they were hiding behind, killing Walter. He was extremely unlucky as the Troop had not been seen by the Germans and the shells were probably ones that that misfired.

Walter was buried in grave 23.H.5 of the Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Nijmegan. For Walter’s family, the celebration of Boxing Day was forever marred by his death.

Walter’s brother John (1910-1985) continued to run the Farm at Gill Edge, along with his wife Ruth Mason, whom he married in 1938. His brother Percy (1912-1973) married Annie Raw in the same year and Percy worked as a dairy farmer, living in Bainbridge in the 1940s. No details are known about Walter’s siblings Henry Gilbert (1915-1985), known as Harry and eldest sister Margaret, known as Jenny (1908-).

Pilot Officer George Daykin Cockbone, 175 Squadron, Royal Air Force

George’s family had lived in Bainbridge for at least four generations. His father John owned a lot of property in the area, including the Corn Mill. During the 1920s the corn mill became a cheese dairy and the family lived nearby. John also kept animals on land near Semerwater and had a butcher’s shop in Bainbridge, with a slaughterhouse behind.

John married Alice Daykin from Nappa Scarr and the couple had 11 children – 2 girls and 7 boys survived to adulthood with George being the second youngest. Eldest Richard became a butcher and took on the shop, Guy a cattle dealer, Harry a stockman and Kenneth a policeman. George became a mechanic and his sister Doris married butcher Reginald Allen and youngest sister Margaret married motor mechanic Harry Metcalfe. It is unclear what happened to his brothers John and Sidney.

Initially George went to Bainbridge School, followed by Yorebridge Grammar School before an apprenticeship at Kettlewell’s Central Garage in Hawes. Growing up he had developed an interest in motor sport, and motorbikes in particular. He even became a semi-professional speedway rider during the late 1930s. The Cockbone Cup was presented as a prize at Bainbridge Sports for Motorbike racing in recognition of George’s dominance of this event in the 1930s, when he was the only rider to reach the top of the motorbike hill climb, which he often did standing on the seat of his bike! His dare devil attitude made it inevitable that he would join up soon after war broke out and he joined the RAF as a fighter squadron pilot.

At the beginning of 1940, he married Beatrice Jean Fawcett, known as Beatty, who lived in Dent, at the church in Cowgill. The couple lived at Spice Gill, Dent and were joined by their son, Desmond, in the summer of 1940.

George joined 175 Squadron and in mid-1942 was based in southern England initially flying Hurricanes. Later in the war, the squadron were supplied with Hawker Typhoon fighter planes, which were rocket firing and were often used as ‘tank busters’. On 2nd June 1943, the squadron moved to a new base near Chichester in West Sussex.

Just over two weeks’ later, George took off from the airfield in Typhoon EK184 on a fighter sortie mission against opportune targets on the ground. The RAF slang for this was a ‘rhubarb mission’. He crossed the English Channel and then the French coast a little west of Dieppe. He flew at low level inland looking for targets on the railway line or military vehicles on the roads, and whilst doing so was shot down with no chance of using his parachute to escape.

His plane crashed near Motteville, around 20 miles south of Dieppe. He is buried in grave H.57 in the Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery.

Corporal Jack Hindle, Royal Army Medical Corps, 6th/10th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, Parachute Regiment

Lewis Hindle was born in Halifax but moved to Bainbridge with his wife and young family in 1927. Lewis worked as a carter initially, and married Harriet Holdsworth in 1904. Their daughter Ellen was born the following year. The young family moved to Blackpool, where Lewis worked for Cash’s bakery, initially as a delivery driver and then learning the business. Their son, Jack, was born whilst they were in Blackpool and was 8 when they moved to Bainbridge, where Lewis opened a bakery at the top of the Green. Just 7 years later, Lewis died of TB, leaving Harriet and Ellen to run the business. As well as the bakery, which also had a café within it, they opened a grocery shop in Askrigg. In the 1939 census, Jack was listed as the baker and delivered the bread across a wide area.

Jack had gone to the village school and then on to Yorebridge Grammar School. He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps at the start of the war and was sent to France with the British Expeditionary Forces, tending the wounded in an army field ambulance station before being evacuated at Dunkirk.

Jack had been courting Irene Fawcett, the daughter of John & Martha Fawcett of Nappa Hall, near Askrigg and on 11th October 1942, whilst on leave, Jack married Rene at St Oswald’s Church. Initially, Jack was stationed on Salisbury Plain, and Rene followed him and worked at an aircraft factory.

Jack’s captain was keen for greater military action and volunteered his unit for training to go into action with the newly formed Parachute Regiment. In the middle of 1943, the 6th/10th Parachute Regiment were in the Mediterranean and Jack was with them and was there in November that year when his daughter Anne was born.

Jack had not been involved in fighting in North Africa, but had been training hard with the Parachute Regiment, undertaking three practice jumps. The unit were expecting to take part in the invasion of Sicily, but whilst waiting on the plane to take off, their mission was cancelled. Instead, the unit headed for Italy, sailing across the Med to Taranto. Arriving at the harbour, Jack’s ship was the first to arrive and most of his colleagues were on deck getting their kit together. A sudden and violent explosion ripped through the ship, which split in half as the ship hit a mine. Jack and around 20 other men were below decks at the time of the explosion. It was dark and the water began pouring in, when Jack took charge and got the men moving out in an orderly fashion. He remained below decks until he was sure everyone had escaped. He was recommended for a medal, but nothing ever came of it.

On 1st December 1943, they were in central Italy and were sent into the line for the next six months. Jack worked hard picking up the wounded under shell fire and displaying coolness under fire and good judgement. He is described by his commanding officer, Captain Stock as being considered by the men as ‘our doctor’.

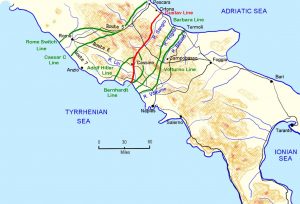

The unit were involved in the Battle for Cassino but were brought back to Salerno to prepare for a parachute drop behind enemy lines north of Cassino. The plan was to get into position behind the main German supply route in that area and then destroy the German transport. Two medical Corporals and two orderlies were to be sent in with the main force and because Jack was one of the best, he was chosen for the mission. The parachute drop was successful, and the team climbed over the mountain ridge into the next valley where the supply road lay. They had moved over night and the following morning they split into four parties to complete their mission. Jack remained high up in the mountains with the headquarters of the unit, whilst the fighting patrols moved and worked at night and hid during the day to avoid detection.

The cover was less than expected and the Germans reacted strongly, sending a brigade in to try to find the British Parachutists who were disrupting their supply lines. On 4th June, a German patrol came across Jack and a few other men and, after a brief fight, overcame them. Jack was shot through the head and died instantly. Some of the British escaped and came back the following day. Jack’s body was found and was buried in those hills on the side of the main road some 40 miles north of Cassino, which is where he remains.

He is commemorated on Panel 12 of the Cassino Memorial, Italy.

Jack never got to see his daughter, Anne who lived at Green View in Bainbridge with Rene until her marriage in 1966. Jack’s elder sister Ellen married Norman Willis just after the war and the couple remained in Bainbridge.

Sergeant Pilot Sydney Chapman Kirkbride, 37 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Sydney was born on 16th August 1915 in Askrigg, the eldest son of Thomas and Isobel (nee Chapman) Kirkbride. His father was a dairy farmer and cattle dealer, just like his grandfather before him. Thomas often travelled through Swaledale buying cows and sheep and on occasions he was accompanied by Syd and his brother Thomas junior (1917-2007). Syd’s grandmother, Mrs Chapman, was also responsible for his upbringing and said that he was a kind and sensible, caring lad and she thought the world of him. Syd and Thomas had a passion for trainspotting, often visiting the station at Garsdale or sometimes even as far as Danby Wiske on the East Coast Line. Syd also two sisters, Margaret, born in 1913 and Esther Shelagh (1924-2010). Syd attended Yorebridge Grammar School and went straight from there to RAF Cranwell as a 17-year-old cadet in September 1932. Three years’ later he was a wireless operator mechanic, but by December 1938 he was training to be a pilot, which he achieved by August 1939, just as war was about to be declared.

During his time in the RAF, he had been posted to Iraq in October 1936 as a wireless operator, based at Air Depot Habbanyia which was on the river Euphrates west of Baghdad and saw service in Palestine. As a sergeant Pilot, he was posted to 37 Squadron at Feltwell in Norfolk on 20 December 1939, flying Wellington bombers. Between qualifying as a pilot and his posting, he married Kathleen Mary Middlebrook in Bradford on 30th September.

Two days before Syd joined the Squadron, six Wellingtons from 37 Squadron had joined in a disastrous raid to locate German warships along the coast of Heligoland. They were attacked by enemy fighters and five of the six Wellingtons were shot down.

The Wellington was barred from taking part in any such future raids and instead the Squadron concentrated on attacking targets in Northern Europe – most of them being night bombing missions, as well as targeting sites in Norway, during the period of the German invasion of that country. Sydney’s worst flying experience so far came on one such raid, when a heavy snowstorm forced them to fly dangerously low to try to avoid the worst of it.

Much of what we know about the raids that Syd took part in is from his letters home to Kathleen. On 14th May he wrote about participating in night raids, including one on Rotterdam. On 22nd May he wrote ‘very busy lately and four flights out of six have been on bombing raids destroying railways and bridges. We were out on Wednesday, Friday, Sunday and last night. So, we are doing our share all right. We lost one plane last night, but none on the other trips. Last night we were in Aachen in Germany bombing railway sidings. Did you hear it on the 1 o’clock news today?’

In his next to last letter some of the fatigue of constant missions is evident. He wrote ‘I feel much better than I did yesterday. I was awfully tired when I wrote to you. I can’t for the life of me sleep through the day, but I shall see the doctor soon and he’ll probably be able to help me. Apparently, I’m not the only one who suffers this way’.

Within days of this letter, Sydney was dead. He flew regularly with Sergeants Charles Read (aged 20), John Francis McCauley (aged 25) and T Johnson and Warrant Officer George John William Grimson (aged 32) in Vickers Wellington L7792. At 10pm on 14th July 1940, their Wellington, piloted by McCauley, with Syd acting as navigator, took off from Feltwell for a raid over Hamburg and Bremen, together with 8 other Wellingtons from their unit. The objective was to bomb widespread targets in and around the ports, including the marshalling yards in Hamm and the oil storage depots in Bremen. The weather and visibility were good, and all aircraft identified the primary targets. One plane failed to return and that was Wellington L7792. The captain of a New Zealand plane reported seeing a Wellington shot down close to Bremen.

This was indeed L7792 which was shot down by the No 1 Flak Reserve at 182 Blumental-Bremen. Three of the crew, including Syd, were killed whilst Sergeant Johnson and George Grimson were taken prisoner by the Germans. Sidney, McCauley and Read were buried with full military honours by the German army in Bremen, but after the war they were moved to Becklingen War Cemetery near Soltau, between Hamburg and Hannover. Johnson and Grimson were imprisoned in Stalag Heydekrug, but Grimson escaped and was on the run for a while. He was never seen alive again and it is thought he was caught and shot by the SS sometime in 1944.

The news about Syd was received at home by his wife, Kathleen and 12 days later gave birth to a baby daughter. Desperate for news of what happened, Sydney’s mother wrote to the father of one of the crew members who had survived and was taken prisoner. Eventually on 16th March 1941 Sergeant Johnson, Prisoner of War, wrote this letter to Isobel Kirkbride.

‘Thank you very much for your kind letter. My father has told me that you were writing to me, and I was very glad to hear that he had written to you and was able to put your mind at rest by letting you know what happened to Syd. I can hardly believe that Syd has gone, for I have flown on his crew all the time. I always experienced the upmost confidence in his ability as a pilot. I shall always remember Syd by his cheerful smile and optimistic attitude during moments of great danger, it made me feel proud to be flying with him.

We were victims of a direct hit, which struck the cockpit, the pilots received the full force of the blow, killing them instantly. The only survivors were the rear gunner and myself, who escaped by parachute. Syd was buried with full military honours in Bremen. I was unfortunate to be in hospital at the time. I gained details of the funeral from a guard who described it was ‘a procession worthy of a gallant flyer’.

No words can express the deep sympathy I feel for you. But as you say, we have many happy memories of Syd, these are immortal’.

Syd’s widow Kathleen and her daughter lived in Bradford. Kathleen remarried around 1960 after her daughter’s marriage in 1959.

Lieutenant Frank Vernon Percival, HMS Barham, Royal Navy

Arthur and Caroline Percival arrived in Askrigg around 1935 and lived in Main Street with their daughter Anne. Arthur had been born in Swaledale but had moved with his family to Burnley in the late 1880s. He had joined the police force, risen through the ranks and retired as a superintendent after 30 years’ service just before the move to Askrigg. In 1910, he had married Caroline Waddington and the couple had two children, Anne and Frank. Anne was born in 1911 and became a hairdresser, setting up a business in Askrigg whilst she was here. Frank was born in 1915 and was a bright and able student and after school went to London University, where he attained a BSc (Hons) and worked as an engineer for an electricity company in Sheffield. At the weekends he would drive to Askrigg to spend the weekend with the family.

Frank joined up near the beginning of the war as a sub-lieutenant in the Navy and rose to rank of Lieutenant on the HMS Barham, which was a WW1 battleship, and he oversaw the engine room. The ship was part of the cruiser/carrier force in the Eastern Mediterranean led by Admiral Cunningham in 1941.

Activity in the Med was intense. Fighting in North Africa and Italy and the anticipation of attacks in the Balkans and Greece meant that the sea was full of troop carriers and supply ships. Where these were, submarines and aircraft followed and both sides were suffering shipping losses. Twelve extra U-boats were sent to the Med in November 1941 and soon had a devastating effect on the Royal Navy. On 12th November, HMS Arc Royal, an aircraft carrier with a full complement of aircraft and men, was sunk by torpedoes.

At 4.25pm on 25th November, HMS Barham was hit by three torpedoes from U-331, which struck from close range and impacted on the ship’s port side. Immediately the ship listed heavily to port and 4 minutes later, her magazine blew up. She sank quickly with the loss of 862 men, about two thirds of the crew. Survivors were picked up by HMS Hotspur and included Vice-Admiral Henry Pridham-Wippell.

The sinking of the ship was captured on camera for Pathe news by a reporter on board another ship, but it was not shown for some time as the news of the sinking was kept from the public as the dramatic footage was thought to be a threat to national morale. The commander of the U-boat, Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross by the German High Command for his actions that day.

No bodies were recovered from the Barham, which remains where it sank, around 200 miles off the Egyptian coast, west northwest of Alexandria. Frank’s body was never found but he is remembered on the WW2 memorial here in Askrigg, and also on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial (Panel 45, column 2).

Frank’s family moved away to Blackpool and his parents died in the 1960s. Anne died in 1983.

Major David Charles Banks Shorter, Gurka Rifles

David’s grandfather, Alfred, was born in the City of London, and became a schoolteacher. In early 1870 he was lodging in Over Darwen in Lancashire and working in a local school and fell in love with a fellow schoolteacher, Sarah Spencer, from Burnley and the couple went on to have four children, Harry, Ivy, Sydney and Rennie. Ivy died as a child, but the boys all followed their parents into the teaching profession with Harry and Rennie working in secondary schools and Sydney becoming a physics lecturer at the University of Leeds.

Growing up in Manningham and then Shipley, both suburbs of Bradford, Rennie studied Classics and then science at Cambridge University, afterwards teaching in Taunton and then Northallerton. On 23 April 1910 he married Mabel Banks, a farmer’s daughter from Kilburn. In 1922 the couple moved so Rennie could take up the position of Headmaster at Yorebridge Grammar School. With them came their children Renee, born 1911 and David, born just after their move to Bainbridge.

After going to school at Yorebridge, David went to Durham school in 1935 and was an active member of both the rugby and cricket teams. His father had served in the Royal Engineers during WW1 and David signed up in 1940 when he was 18. He was commissioned in 1941 and was posted to India the following year. He was in action on the Indo-Burmese border and in Burma as a major in the Gurkha Rifles.

David married Audrey in Lahore on 28th April 1945, and he remained with the army after the end of the war. He returned to the UK on leave in 1947 and he was taken ill as he was about to get on board a ship back to India from Liverpool on 3rd May. The passenger manifest for the P&O ship the Scythia lists David as a passenger headed for Bombay but shows he did not sail with the ship. Instead, he was taken to the Northern Hospital in the city where he died later the same day.

The post-mortem shows that he died of a subarachnoid haemorrhage, probably from a congenital aneurysm in the circle of Willis. His body was cremated on 6th May in Liverpool. He was 25 years old.

Rennie died in 1956 and his wife in 1973 and a memorial to them and their children stands in Bainbridge cemetery.

David’s sister, Renee had married Thomas Dawson Whaley in Askrigg in 1934 and they lived in Rookhurst in Gayle. Dawson, went to Yorebridge Grammar School, where he had met first met Renee. He trained as a solicitor and was working in Romford, Essex when they married. They lived for a while in Newport, in Shropshire where their daughter Greta was born. Dawson was in the territorial army and joined up when war was declared. He

obtained his commission in the Royal Artillery and was stationed in Northern Ireland. Renee moved to be close by and their son, Thomas was born during this time. Dawson began training for the Normandy landings and was based in the south of England, so Renee, heavily pregnant, took the children home to Rookhurst. Dawson died on 17th July 1944 when acting as a forward observer – he was shelled by Panzer artillery and strafed by the Luftwaffe.

Renee gave birth to a second son, David, a week after Dawson’s death. She married John Fawcett in 1948 and lived in Wensleydale until her death in 2004.

Sergeant Ernest Keith Stevens, 214 Squadron RAFVR

Josiah Stevens was born in Nottinghamshire in the 1880s and was a carpenter and joiner. He married Annie Holmes on 20th February 1909 and six months later their only daughter was born. The couple then had a son, Reginald, who was born on 2nd November 1912, but Annie never recovered from the birth and died two weeks’ later. His young children were looked after by Josiah’s family when he enlisted in the Royal Engineers in 1915, leaving the service at the end of the war as a corporal.

On 25th May 1919, Josiah married Lily Bettison, a 25-year-old schoolteacher from Belper in Derbyshire. In November, Lily gave birth to a son, Ernest Keith, more usually known as Keith. The family moved to the Dales in the 1930s when Lily took up a position as teacher at Bainbridge School. In the 1939 census, the family was living in Bowbridge, just outside Askrigg on the Hawes Road. By then, Reginald, a joiner like his father had brought Winifred, his bride to join the household.

The family quickly settled into life in Askrigg. Josiah had his own carpentry business and helped with the choir at St Oswald’s. During the Silver Jubilee celebrations at Bainbridge in 1935, he was the leader of the band that led the procession. Keith worked at Swain’s shop in Hawes and amongst his friends was Jack Hindle, another name on the WW2 memorial.

When war was declared, Keith joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve and was soon training as a wireless operator and air gunner. He was a member of 214 squadron, based at RAF Stradishall in Suffolk and was flying in Wellington bombers. The bombers from Stradishall were flying missions mainly against naval and industrial targets in Western Europe.

On the night of 1st April 1942, 14 Wellingtons from 214 Squadron and 21 other Wellingtons joined 14 Hamptons to carry out a low-level attack on railway targets at Hanau Lohr, near Frankfurt. Their approach was met with heavy flak and from German fighter squadrons and 214 squadron returned to base having lost half of their bombers.

Wellington Z8805, a Mk1C, was flown by Sergeant Eric Dixon and Pilot Officer Thomas Best, with observer Sergeant Albert Richards, Wireless Operators/air gunners Keith and Pilot Officer James Henderson along with Gunner Sergeant Edward Albrighton. The aircraft was brought down by flak from no 7 Flak-Division just south of Cologne, close to the Rhein at Lulsdorf-Neiderkassel and the subsequent crash killed all on board outright. The crew are all buried in the Rheinberg War Cemetery in Germany.

Josiah and Lily moved away to Kent at the end of the war.